The European Commission launched the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans in 2020. But five years later, progress is limited. In mid-October, an updated Action Plan was endorsed by Western Balkan leaders. Here we look at whether civil society proposals were taken into account and whether the revised plan can inject new dynamism into the process.

Pippa Gallop , Southeast Europe Energy Policy Officer | 6 November 2025

Photo: Ivan Posinjak

Since its inception, the Green Agenda has inspired plenty of conferences and panel discussions, but too few results on the ground. So this year’s revision of its regional Action Plan should have been an opportunity for lively debate.

Civil society organisations were ready to contribute. For example, in October 2024 eighteen groups contacted the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC) – to whom the Commission has delegated the management of the Green Agenda – with detailed proposals on improving the Action Plan and the governance of the process.

In early 2025, the RCC informed civil society representatives there would be a two-stage consultation. The pre-draft one was held in April, but the second one on the draft Action Plan was first delayed, then disappeared altogether, as endorsement of the revised Plan was scheduled for the Dubrovnik ministerial meeting in mid-October.

On 13 October, just before the meeting, 52 civil society organisations wrote to the RCC to express their frustration that no consultation had been held on the draft.

Some clear improvements in the plan

Despite the flawed process, the Revised Green Agenda Action Plan 2025-2030 at least represents a clear improvement compared to the first one.

The first and most visible aspect is the format, which closely corresponds to the one proposed by civil society groups last year. It breaks down the actions into smaller pieces and provides clearer timelines for implementation, as we recommended. It also includes indicators and stipulates, at least for some actions, how their achievement will be verified.

It still has a lot of actions – 41 – and some of them have multiple parts, but at least there are fewer than before, when it had 58. Some new actions have been added, but several less useful and difficult to measure actions have been deleted.

Overall, out of around 63 recommendations we submitted in October 2024 regarding specific actions, around 15 of the updated and new actions to some extent encompass what we proposed. In addition, most of the deletions – 13 – correspond to our suggestions, and some actions do not correspond to our proposals but make sense and are welcome.

Among others, a new action on preparing Just Transition Plans for coal regions in transition has been included, closely corresponding to our proposal, as well as one on mapping existing and potential funding sources for just transition and setting up a regional dialogue on the topic.

A new waste target has also been set: by 2030, the Western Balkans Six will achieve at least 40 per cent municipal waste recycling. This is modest compared to EU requirements, but if implemented would represent a substantial improvement for the region.

But no consensus on deadlines

Many of the remaining issues relate to deadlines, where our opinion on priorities differs significantly from what is in the updated Plan.

For example, the countries will ‘identify vulnerable and marginalised groups with poor access to drinking water by 2028’ and improve access of all citizens to safe drinking water by 2030. It’s good that these issues have been included in the plan, but taking three years to identify – and two more years to fix – a problem as fundamental as access to clean water is too long.

At a time when the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is about to kick in, it also seems strange to take until 2030 to ‘set up all relevant institutions and processes to ensure emission data collection under the EU Emissions Trading System in its full scope.’ If the countries want exemptions for their electricity sectors from CBAM, they will need to have fully functioning emissions trading systems by then, not just data collection.

Biodiversity still lacking adequate legal safeguards

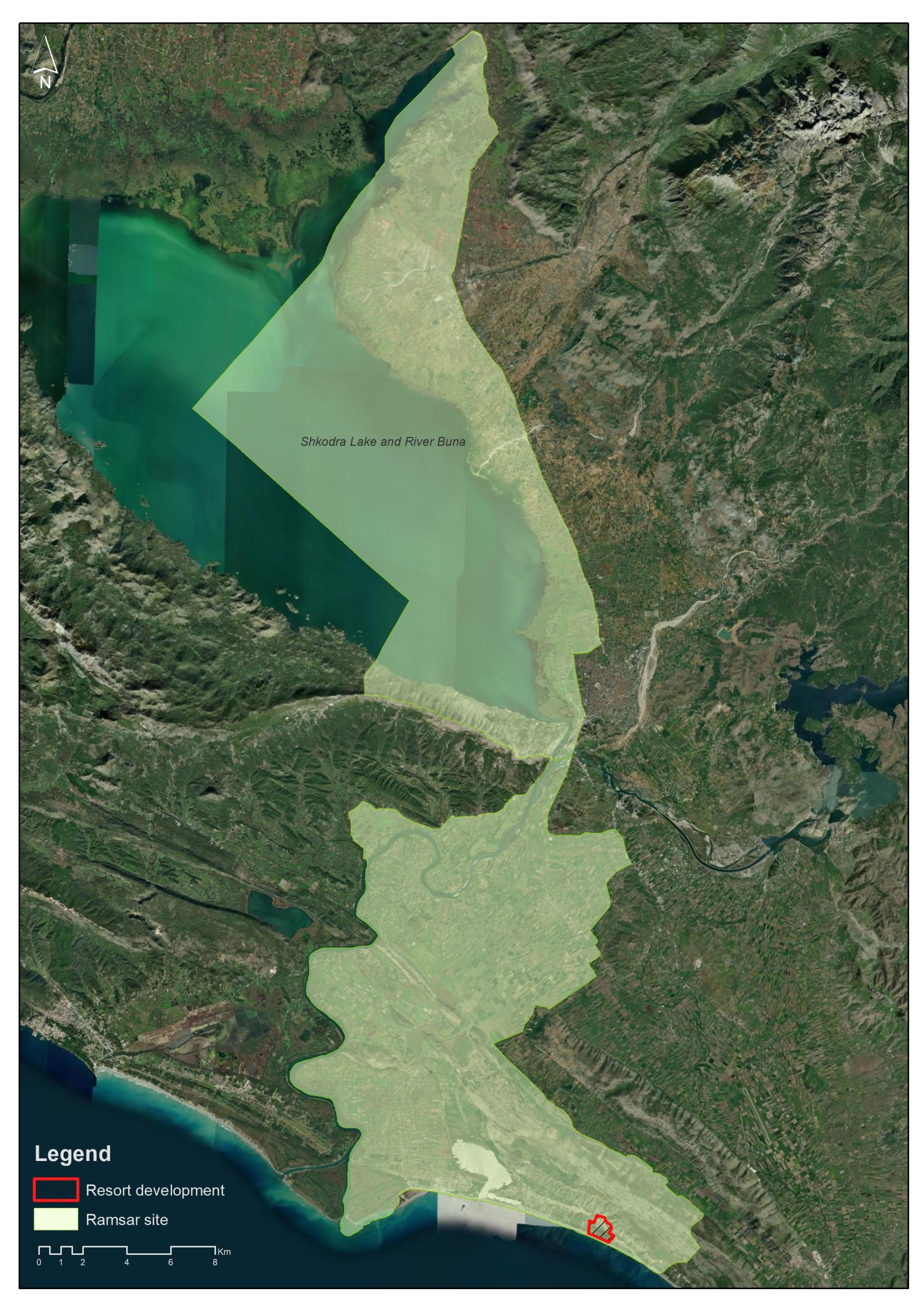

Another remaining weakness is the lack of legislative actions in the Protection of Nature and Biodiversity section, which has not been addressed at all. All the Western Balkan countries need to legally protect their nominated candidate Emerald sites, nominate more sites to develop their ecological networks, and improve the protection and management of their existing protected areas. They also need to strengthen their legislation to ensure that appropriate assessments are carried out for plans or projects that may negatively impact their ecological networks.

The inclusion of developing ‘Quantified objectives to expand protected and conserved areas of terrestrial and marine territory’ in the countries’ nature conservation strategies is a step towards what we asked for, but it’s too little, too late. The countries have specific sites that need protection now and in some cases they have all or much of the relevant documentation prepared already. So legal protection should be ongoing, it doesn’t need to wait years for new strategies and targets.

Without a strong legal framework to prevent harm to biodiversity in practice, softer actions like strategies and plans can’t be effective. The inclusion of nature restoration plans in the Green Agenda is an interesting development, but the emphasis should be on preventing harm in the first place by properly applying the Habitats and Birds Directives. And without transposition of the Nature Restoration Law being stipulated as well, it’s debatable whether restoration plans will have an impact.

Governance and implementation still the elephant in the room

All the above issues could have been resolved, had a meaningful public consultation taken place on the draft revised Action Plan. But the bigger problem, which remained untouched by the revision process, is the Green Agenda’s governance.

Ever since the inception of the Green Agenda, it’s been unclear whether governments have committed to implement specific actions. And its overlaps with existing, more structured initiatives like the Energy Community Treaty and Transport Community Treaty make it more difficult to track progress and understand its added value.

The introduction of the Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans in 2024 could have been an opportunity for the Commission to incentivise Green Agenda implementation by ensuring the inclusion of measures from the Action Plan in countries’ Reform Agendas. But – again partly due to a lack of public consultations – a plethora of energy-related reforms were included, but very few environmental ones. Such omissions must not be allowed to recur if the EU employs similar instruments in the region again.

At this point, it seems separate country-level Green Agenda Action Plans will be needed, to show which actions the governments commit to, by when, how much they will cost and who will implement them. And the plans must be publicly consulted.

But for this, the European Commission has to step in and give them a good reason to do so. Without consequences for non-implementation, the Green Agenda risks remaining all talk and no action – an outcome the region cannot afford.